AI Drivers: Is Tesla going anywhere?

What do we gain and what do we lose with self-driving cars?

This is number 2 of a 10 part series on the ethical building blocks of Artificial Intelligence. In each section I examine the values on which the technology has been built. AI is a tool which can be used for good or evil, but it is not a neutral tool, it has its own values baked in.

Self-driving cars have been dreamed of since cars first appeared on roads. Partially driven by their representation in fiction. From KIIT in the TV series Knight Rider (1980s), Demolition Man (1993), iRobot (2004), a stream of Batman, James Bond and Transformer films where the car is either a character in its own right, or a trusty steed which adds to the heroics of the diver. Self-driving cars have been synonymous with the future. Tesla is the closest to making that fantasy a reality.

Automation exists in much of the driving process; automatic gears, sensors, automatic braking systems, parking assist. But we don’t have a self-driving car yet. Even the most autonomous self-driving cars zipping around California’s roads are only level 3 on the 5 levels of autonomy. To be level 5 it has to be fully self-driving, anywhere a human could drive.

But while we know what we gain from self-driving cars, are we aware of what we will be giving up? And is it worth it?

Self-driving cars are built on the following values:

Computer vision – everything can and must be categorised.

Privacy is dead – everything is recorded.

No one is responsible when someone dies.

Convenience is king.

We will examine each of these in turn, but first we have to understand how the technology actually works.

What do we mean by self-driving?

A car that uses hardware such as sensors, cameras and radar (the eyes of the car) to feed information to AI software (the brain) so that software can tell the car what to do. It should be able to make any journey a human driver can, but more safely and more efficiently.

The dataset

Self-driving cars are trained on vast datasets until the AI can reliably label a cluster of pixels as a specific object. For Tesla, this dataset is constantly being added to by its fleet of cars, whose owners act as driving instructors for the AI software, teaching it how the driver reacted to different objects. Other manufacturers use things such as simulations or pre-recorded videos of journeys to educate the AI.

Computer vision

Self-driving cars use technology called “Computer vision”. Seeing is difficult to program because sight involves perception. The brain is as important as the eye to seeing. A good camera is not enough for a computer to “see”.

Machine learning algorithms are used to enable the computer to teach itself to “perceive” images in the dataset.

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) deconstruct images and use machine learning to extract features at the pixel level. These groupings of pixels are then labelled. The AI is fed correctly labelled images and infers the rules of identification. Learning over time to assign more weight or bias to specific features to make a more accurate prediction.

For a very accessible but detailed breakdown of how computer vision and CNNs work I recommend reading here.

Categorisation

So in order to be “seen” an image must be labelled and categorised. Everything “seen” is categorised. This is done through a % likelihood. A computer is rarely 100% confident an object is a pedestrian – but it says “This set of pixels is a 99.89% match to other sets of pixels which I have been told to categorise as pedestrian. So, this is probably a pedestrian.” The computer does not know what things are – it just compares them to its vast library of previous images. If there were no images of pedestrians in the training dataset, when it encountered one, it would not label it as a pedestrian. We will come back to some of the ethical challenges with categorisation shortly.

The action

Once items have been categorised then the program can dictate what action should be taken upon encountering them.

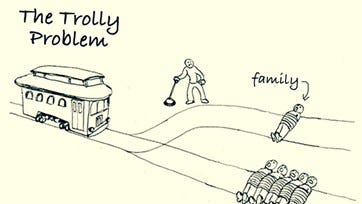

The Trolly Problem

This is the area of ethics where most debates around self-driving cars end up. Imagine an out-of-control trolley barreling down some tracks upon which 5 hapless people are tied. There is a lever in front of you which would change the trolley’s path, diverting it to a track with only one person. Do you intervene and actively participate in the death of one person or do nothing and passively participate in the death of five?

Now imagine that the trolley is a self-driving car, and instead of tracks it encounters an overturned truck, leaving it with the option to smash into the truck and kill its passengers, or to swerve into the pavement and kill the gathered crowd of pedestrians. The car does not make this decision in the moment, a programmer designs the algorithm in advance. Does the equation change on victim age? Gender? Criminal record? Charitable giving record? Insurance? Are car manufactures incentivised to prioritise the vehicle passengers over pedestrians?

Should the programmer make the decision? The car manufacturer? The government?

An MIT project allows you to play out scenarios for who an autonomous vehicle should kill and compare your decisions to previous players. It provides an insight into the ethical challenges of programming the action for the vehicle to take. The results vary widely by country and demographics of the player, highlighting some of the ethical challenges.

This question leads us on nicely to our first moral building block.

Computer vision – everything can and must be categorised.

Computer vision needs to categorise something to “see” it. This is a problem. Firstly, because of bad training data, computer vision is often bad at categorising things correctly. For example, a 2015 study found facial recognition software was accurate to a 1% error rate for white men, but at 35% error rate for black women. If you can’t audit the training set, how do you know what a car can “see”?

Secondly not everything can or should be categorised. Categorisation if often deeply reductive.

Even objects are not merely the sum of their labels, and humans most certainly are not. I find it striking that the rise of computing and the imperative to categorize increasingly nuanced facets of the human for the big data marketplace has coincided with the rise of identity politics. We are increasingly content to view ourselves through the one-dimensional computer lens.

How does this relate to self-driving cars? Well if the car can’t “see” a black woman - because black women weren’t adequately included in the training sets - that could be lethal. It also brings us back to the Trolly problem, if you are categorised as a certain type of person, and then more value is ascribed to that kind of person in the trolly problem equation, you can see how the process of categorisation itself becomes a problem.

Privacy is dead – everything is recorded.

The self-driving car needs to be constantly aware of its surroundings. This means it is constantly recording video, location, interaction with other cars, speed, driver… the list goes on.

A lot of good can come from this. It cannot fall asleep, be drunk, check its phone or even blink. There would be fewer deaths and fewer accidents, one report predicts accidents would drop by 90%. Traffic could also be a thing of the past as vehicles communicate with each other and adjust routes and speed.

But there is a flip side. Police already use dashboard cam footage if a car has driven past a crime; they would use driverless car footage too. Companies and police could know every journey you took, who you visited. The right to privacy underpins the right to freedom of association, which is a core part of freedom of speech and indeed democracy. All driverless cars are tracking devices which the manufacturer and potentially the government can use, to sell to you and to police you.

No one is responsible when someone dies

The first fatal crash of a self-driving car killed its driver Joshua Brown. This sentence is both tragic and contradictory. How can a self-driving car have a driver? Tesla described the cause of death as a failure of both the “Auto-pilot” system and Joshua Brown “the driver”, but said it was “the driver” who had responsibility for the crash.

Arguably cars are only “self-driving” when no one in the car is responsible for its actions. The car is the driver. But if a “self-driving” car makes an error which results in injury or death, it cannot go to jail. If the car cannot be held accountable, it is never actually self-driving. A more accurate term might be “algorithmically driving”.

So, does that then mean that the algorithms programmers are legally and morally responsible for the accident? Or the car manufacturer who allowed a flawed system to be sold? Is it the CEO or the shareholders who are ultimately responsible?

This is called the problem of many hands. When something terrible has happened, often due to a series of human errors but no one individual is responsible. In the past leaders often accepted some level of moral responsibility but this is less and less the case.

Despite being a car company, Tesla has employed the iterative, fail fast design principles of software development. Fail fast takes on a different meaning when safety features in your car have failed as you travel at 60 kph.

Convenience is King

Cars have revolutionised the world. Individual movement is now convenient and cheap.

But there are trade-offs. Air pollution, noise pollution, car-centric design of our cities and towns, and of course a huge number of road deaths. In 2019, 1752 people died on UK roads. It used to be much worse, in 1979 6352 people died.

These trade offs are not inevitable, manufacturers chose them because they reflected the values of the time. To begin with cars had no seatbelts and were less green to run, safety and the environment have become more important, so the design has changed. But we are still comfortable with cars designed to travel well over the legal speed limit, or we are unwilling to switch to electric due to fears around the inconvenience of charging. For many, convenience still trumps climate.

And what problem do self-driving cars really solve? Better public transport would be a much better way to reduce traffic, accidents, and emissions than self-driving cars. Trains would still be greener than self-driving trucks. Considering the limits of self-driving cars they may only ever be suited to UK motorways. So, if you must drive yourself to a motorway, why not a train station? Because it is just less convenient, less easy. Our society places an incredibly high value on convenience. All the money invested in self driving research and infrastructure would deliver greater societal returns in train and bus networks, except for convenience.

So, are self- driving cars artificial?

Today, no car legally allowed on the road is fully self-driving, they all rely on the human driver. Humans have also coded the cars actions in advance. In the case of Tesla, human drivers are constantly training the cars. So even though it is not the human in the car doing the driving, it is still human driven.

Are self-driving cars intelligent?

They can identify and predict action, so they are “smart”. But they cannot imagine or adapt. They cannot “see” it if they cannot label it, so unpredicted events cause them to fail. The car cannot imagine what might happen next, imagination is different than prediction. Self-driving cars are deeply smart, but they are not intelligent.

Are self-driving cars ethical?

While, self-driving cars solve some ethical problems, they are not the best solution, and they introduce their own new problems. So, I would say they are a force for good, but only just. Not good enough for me to go out and buy a Tesla, but I’ll still probably ask my brother-in-law for a lift in his.

If you enjoyed this article, please consider reading others in the AI ethics series.

1. AI knowledge: Is chatGPT smarter than you?

2. AI drivers: Is Tesla the going anywhere?

3. Facial Recognition – AI Big Brother? 4/3/23

4. Dr. AI? 11/3/23

5. The bank of AI? 18/3/23

6. Algorithmic decisions – Bureaucracy of AI? 25/3/23

7. Chatbots – AI friends? 1/4/23

8. Deepfakes – AI faces? 8/4/23

9. Targeted marketing – The AI nudge? 15/4/23

10. Generative AI – The AI artist? 22/4/23