AI can see you: Facial Recognition is watching.

The good, the bad and the ugly of facial recognition technology.

This is number 3 of a 10 part series on the ethical building blocks of Artificial Intelligence. In each section I examine the values on which the technology has been built. AI is a tool which can be used for good or evil, but it is not a neutral tool, it has its own values baked in.

Facial Recognition Technology, or FRT, is already woven into our lives. It is used by police, your bank, private landowners, your mobile phone, schools, border force, your doorbell…the list goes on. For some, it is the ultimate tool of accountability, ensuring criminals are caught and that police don’t abuse their power. To others is it a dystopian tool of control, invading your privacy and anonymity in public space, the all-seeing eye of authoritarian regimes.

As with any tool – FRT can be used for good and for evil, depending on who is using it and what for. But the technology has inbuilt values which mean that some outcomes are more likely than others.

Facial recognition technology has these three values baked in.

The camera is accurate and neutral.

A record is a good thing.

A picture tells a thousand words.

But first how does it work?

Facial Recognition uses computer vision alongside machine learning to identify and match faces. The computer does not see a face as a human might, but instead converts facial features into data which can be stored, interrogated, and matched with other data using the following steps.

Identification: Detecting a face within an image.

Analysis: The software identifies facial landmarks and converts these into geometric points, creating a map of the face.

Example construction of a facemap

Datafication: The face maps are converted into data using mathematical equations. This creates a unique identifier.

Examples of Facemaps

Match: A determination is made if there is a match between the facemap the computer has “seen” and any facemaps stored in existing image data bases. The outcome is a probabilistic assessment of the likelihood of a match.

The camera is accurate and neutral (The good)

The camera doesn’t lie. Except of course it does. Almost every image which has travelled to you through the lens of a camera is different from how it would appear if you had seen it with your own eyes. Photoshop, cropping, filters… and that’s before you get into the realm of ‘deep fakes’, and editing hypothesised in the Chanel 4 drama “The Capture”.

TV drama The Capture imagines a world where CCTV images are manipulated

Are Facial Recognition Technologies accurate?

Manufacturers such as NEC, who provide FRT to UK police forces claim to guarantee over 99% face-recognition accuracy in real-world situations. But independent studies have found the accuracy of FRTs is often much lower. Facial obstruction, face angle and lighting can interfere with the software’s ability to create a face map. In the US the ACLU conducted a test of Live FRT which falsely matched 28 members of Congress with mugshots. There is considerable variation in accuracy, with one study finding that some manufacturers accuracy scores were as low 40% and others as high at 87% in similar conditions.

Make-up, accessories and clothes can also make FRT less accurate.

Are Facial Recognition Technologies neutral?

Spoiler alert: No. There is a saying amongst AI developers “Garbage in, garbage out”. It all comes back to the data. The machine learning algorithms need to be trained on high quality and diverse datasets otherwise they struggle to recognise faces which are different to the ones they have been trained on. You won’t be surprised to hear that the first known arrest due to inaccurate FRT was a black man in the USA. One study concluded that white men were inaccurately identified by FRT 0.8% of the time compared with darker skinned women, who were misidentified 34.7% of the time. And frankly when it could lead to you being arrested even 0.8% is still too high.

So why have I called this bit the “Good” bit?

Believe it or not the inaccuracy and bias of current FRTs is the “good” part of this story, because it is the bit we can and must change. Quality, varied data, which can be audited should eliminate bias in FRTs. Quality in, quality out. The same for accuracy, as the technology improves it should get more accurate. However, we should not assume that this progress will just happen with time. As far back as 2009 HP laptops failed to recognise black faces. By 2015, a lifetime later in technology development, Google launched a photo app which tagged black people as “gorillas” and Flickr labelled a person as an ape due to the colour of their skin. In 2019, a poor facial recognition match resulted in the imprisonment of an innocent black man in New Jersey. Time has not solved the bias. Regulation and social pressure drive technology improvements as much as innovation and time.

A record is a good thing. (The bad)

There is always a tension between the individual’s right to privacy and security. Proponents of FRT argue it will lead to a crime free society. But who will watch the watchers? We may feel comfortable sitting in a Western democracy claiming we have nothing to hide. But the idea that “keeping a record” is good, is an inbuilt value.

One of the greatest atrocities in human history was facilitated through the use of mundane record keeping. Nazi’s identified their Jewish victims by pouring over records such as census data, tax returns and synagogue membership lists. Tragically, much of the data used to identify people was data created before Nazi’s swept across Europe, by the victims themselves or their societies in the name of good governance. The problem with creating and retaining a record, or data, is you are betting that the future will be at least as good if not better than the past. This is not guaranteed.

We all create thousands of data points daily as we carry around our phones or browse the internet, and for now this is used mostly to try and sell you stuff. You can always turn off your phone or put your laptop down. But Facial Recognition is different, you can’t turn off your face. As with other biometrics such as fingerprints or retina scans, they are permanent and harder to change than other personal data. Unlike fingerprints and retina scans, faces can be captured on mass scale.

In the UK shopping centres such as the Trafford Centre in Manchester have been monitored by FRT, allowing them to capture the faces of over 15 million people in a 6-month period. If you have been to King’s Cross Station between 2016-2018 your face has been captured by the private company who owns the land and was using FRT across the space. If you have children their school may be using FRT like some in Scotland, to speed up paying for lunch at the school cafeteria.

Signs posted outside the Trafford Centre when FRT was being used. Does walking past this count as informed consent?

Facial Recognition Technology is being used in sports stadiums and theatres to stop “unwanted persons” from attending. But “unwanted” by whom? Maddison Square Gardens, who own venues across the US have been using facial recognition software to ban entry for lawyers who have represented individuals in legal cases against Maddison Square Gardens, including cases of sexual harassment and employment discrimination. So here you have a private company, using FRT to punish people and discourage legal action against them.

Even the knowledge that a record is being kept can change our behaviour, and not always for the better. When you are on zoom your facial expressions are very different than they are when you are not being watched. Facial Recognition technology means we face a future where life is just one long zoom meeting.

For some people that is reality right now. Employers are monitoring you through your webcam when you work from home. Logging minutes of “inactivity” or when you are not sat in front of the screen. The problem is typing or sitting in front of a screen is not a particularly good indicator of whether you are being productive. You can be thinking away from your screen, in fact most people think better.

Record keeping is only prudent so long as we can trust those who keep the records. For this we need to ensure FRT is only in the hands of authorities who are fully accountable and free from corruption now and in the future. I don’t know of any such society – do you?

A picture tells a thousand words. (The ugly)

An image is actually a very limited descriptor of what is happening, you don’t get the wider context out of shot and you cannot understand what the people in the video are thinking, even if you can watch what they are doing. Or can you?

There is a growing field which looks to extrapolate people’s interior thoughts and emotions from physical “tells”. While researching this article – any time I typed in Facial Recognition – I was fed an advert for FaceReader. FaceReader claims to be able to analyse faces and tell you to 100% accuracy if that person is experiencing a range of nine emotions, such as happiness and anger. Including for children and babies.

“Whether your test participant is a baby, a child, an adult….”

This type of technology is being used in schools, shops and law enforcement in an attempt to understand the inner workings of someone’s mind, based on their face. This is problematic.

Think back to how Facial Recognition Technology works - deconstructing a face into geometric shapes and patterns using mathematical formulas. This is reasonably untroubling if you use that to try and find an identical match in an data base – the “recognition” part of the technology. Where it becomes deeply problematic is if you try and use a mathematical formula to do anything else, for example to try and categorise that face.

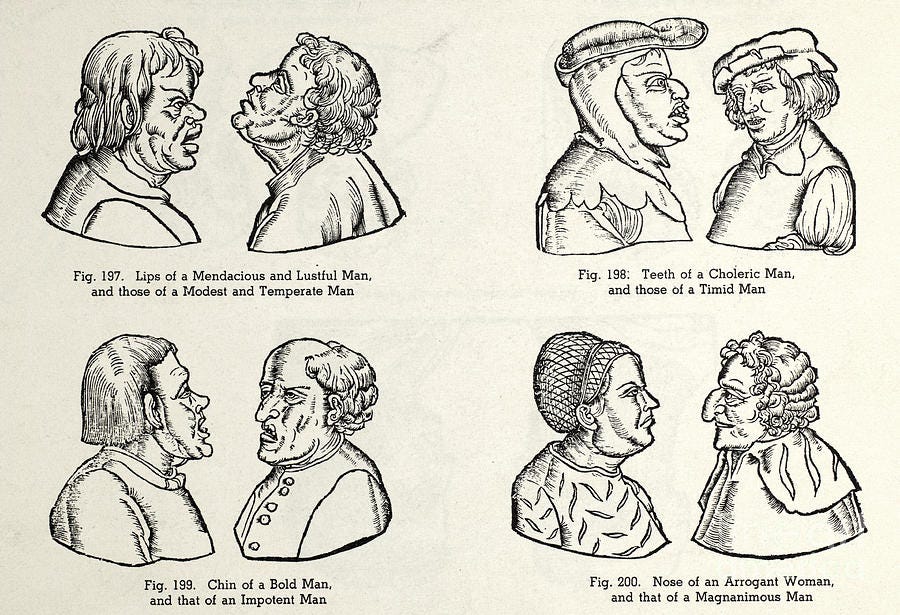

Categorising human faces through mathematical formulas has a dark history.

In the 1800s placing mathematical formulas alongside photography supported the development of phrenology (pseudoscience of measuring skull shape to predict mental traits), physiognomy (attributing personality or character to a person based on outer appearance, especially the face), and eugenics (attempts to alter the human gene pool based on promoting traits deemed “more desirable”.) For an excellent and detailed examination of the issues with using mathematical formulas to classify human faces I suggest reading Excavating AI.

Physiognomy, debunked and discredited is creeping back into our discourse.

Applying a mathematical formula to categorise humans has seen a resurgence in this century. In 2017 Stanford researchers claimed they had developed AI vision technology that could tell if someone was gay. Deeply intrusive anywhere, potentially fatal in countries that criminalize homosexuality. AI is being used to assess social media videos in an attempt to diagnose neurodiverse traits such as autism in children.

The technology does not stop at traits, but attempts to assess emotion and future intention. “Emotion Analysis” is being hailed as a new development in consumer insights and marketing. Police forces have hypothesised that emotion and posture recognition could be used to “decode human behaviour” and identify a person intending to commit a crime. A paper released in 2020 claimed to be able to use a person’s face to predict future criminality to an 80% accuracy.

There are two major issues with this predictive technology.

One is that it doesn’t work. This is largely due to the training data. Often the AI is trained on “staged” or “posed” emotions. If someone says, “look happy!” I guarantee the face you pull won’t be the same as when you actually are happy.

The second is what if it did work? Can you imagine a world where your private inner monologue was revealed to those who are watching? What would it mean for freedom of speech? For freedom of thought?

So, is facial recognition Artificial?

The data being collected must be labelled by someone and someone must teach the AI to categorise it. A human is choosing the categories and what goes into them. The machine is merely doing the sorting. But the scale and speed at which the sorting is done is very much artificial.

Is facial recognition Intelligent?

Not yet. The data sets are not developed enough. They contain inaccuracy and bias. But it will be possible with training and data for a machine to recognise a human face, or even recognise human traits or emotions. We must then ask ourselves is recognition the same as understanding?

Is Facial Recognition Technology ethical?

No. That is not to say there are no benefits. FRT could reduce crime in monitored areas, act as a deterrent and lead to more arrests. In time it may remove the bias and inaccuracy of human witnesses. But there are other ways to achieve these noble aims which do not hold the risks of Facial Recognition. FRT could create a permanent record of your inner and outer self, which can be harnessed by private companies or governments to identify, track, and change your behaviour. It is already being used, rolled out into our lives unchecked and unregulated. It presents a significant concentration of power in the hands of a few and simultaneously provides an overwhelming tool to identify and stamp out any dissent or attempt to check that power. It is a risk to democracy, society as we know it and our freedom of speech, movement and thought.

If you enjoyed this article, please consider reading others in the AI ethics series.

1. AI knowledge: Is chatGPT smarter than you?

2. AI drivers: Is Tesla the going anywhere?

3. AI can see you: Facial Recognition is watching.

4. Dr. AI? 11/3/23

5. The bank of AI? 18/3/23

6. Algorithmic decisions – Bureaucracy of AI? 25/3/23

7. Chatbots – AI friends? 1/4/23

8. Deepfakes – AI faces? 8/4/23

9. Targeted marketing – The AI nudge? 15/4/23

10. Generative AI – The AI artist? 22/4/23