Dr. AI: The machine will heal you.

For medicine to advance do we have to give up some of our rights?

This is number 4 of a 10 part series on the ethical building blocks of Artificial Intelligence. In each section I examine the values on which the technology has been built. AI is a tool which can be used for good or evil but it is not neutral, it has its own values baked in.

The Doctor won’t see you now, but a machine might. Artificial intelligence is already helping us live longer and healthier lives by using large volumes of data to solve complex problems. Identifying patterns, predicting outcomes, and analysing information at lifesaving scale and speed.

You might be wondering what ethical dilemmas there could be with technology that helps heal people. But all technology has inbuilt values, and require some trade-offs. AI might make healthcare better, but it will also make it different.

AI healthcare is being built on different values to that of traditional healthcare, namely:

- Health must be quantified.

- Privacy must be subjugated.

- The Hippocratic Oath must change.

At this point I would normally examine in depth how the technology works but there are a huge number of different AI technologies being used in healthcare. I will give a quick overview of the three categories I find most interesting.

Patterns, Predictions and Speed.

Pattern analysis - Diagnosis

AI can use Computer Vision and Machine Learning to ‘see’ and identify patterns. (I explain how these technologies work in my blogs on Facial Recognition and Self Driving Cars). AI can recognise patterns that humans can’t. It can recognise those patterns faster. It can be worn on your wrist and tell you information directly, cutting out the doctor altogether. The AI will spot anomalies on the X-ray, ultrasound, MRI, endoscopy etc. It is never tired or distracted so it will only miss what it is not programmed to ‘see’.

COVID NET using computer vision and machine learning to detect shadows indicating lung damage.

There are a breath-taking number of fields where this will save lives. For example in skin cancer, a recent study found that an AI diagnosed cancer more accurately than 58 experts, achieving a 95% successful detection rate compared to the human 87%.

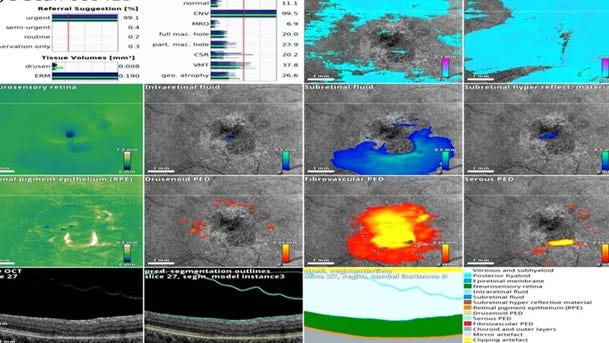

Machine Learning has been used to identify indicators of a future heart attack and diagnose depression. Computer vision and machine learning are being used to detect breast cancer, diagnosis serious eye disease, identify lung cancer, spot early signs of stroke, the list goes on and on and on.

Computer vision and machine learning being used to spot issues in eye health.

Machine learning - Drug development

Machine learning is being used to develop new drugs. Google’s Deepmind made headlines in 2020 by using AI system AlphaFold to predict how proteins fold. Many diseases are linked to the role of proteins in enzymes, antibodies and hormones. Understanding the structure of a protein can help develop treatments for diseases such as cancer, dementia, Covid-19 and a myriad of others. There are billions of human proteins and many billions of others which we interact with including in bacteria and viruses, but before AlphaFold identifying the shape of just one could take years.

A DeepMind model of a protein from the Legionnaire's disease bacteria

As with all tools, the technology can be used for evil as well as good. An AI set up to analyse chemical compounds and suggest cures for diseases was manipulated by users to produce deadly chemical weapons instead. Suggesting thousands of lethal chemical weapons within hour, including compounds similar to nerve agents such as VX.

Behaviour analysis – Monitoring and Prediction

In 2019 AI enabled wearables were used to monitor recently discharged patients from hospitals in England. Armbands monitored vital signs and alerted the hospital if issues emerged. This reduced hospital admissions, emergency room visits, and the need for costly and time consuming home visits.

AI wearables don’t need to be prescribed. Many people now use non-medical AI enabled wearables like Apple Watches to monitor heart conditions, such as arrhythmia.

In fact, healthy people are also using AI to maintain their health. Thousands of Apps claim (often without evidence) that if a user provides their data, the algorithm will be able to predict their health outcomes and direct their behaviour so that they stay healthier for longer.

Apple watch – paying £400 to Apple for the privilege of giving them your medical data.

This list of AI in healthcare barely scratches the surface but gives you the gist that AI can help with diagnosis, research and development and monitoring and prediction.

Now before we look at the values that underpin AI in healthcare, we should do a quick canter through some history of healthcare innovation. It is pretty dark. The point of reviewing the history is not to make us feel bad or guilty but to remind us of moral trade offs and abuses that can exist in healthcare innovation, in an attempt to avoid them with AI healthcare.

Healthcare innovation has historically had two big problems.

1) Ignoring certain groups

2) Using marginalised groups for medical research

Ignoring certain groups

Throughout medical innovation there has been a systematic exclusion of specific groups of people. This particularly affects non-white ethnicities and all women. Every cell in our body has a sex, which means women are different from men on a cellular level. Due to the unsubstantiated belief that variance introduced to female health by the menstrual cycle would skew results women have long been excluded from medical research trails. Not only women, but female animals are also excluded from trails, and even at the cellular stage of research, female cells are excluded. This results in the development of drugs which are specifically designed only for male bodies. This is a fascinating topic and I would highly recommend reading The Unwell Woman for further details. But the point for us to remember is that the historical medical data, at best, gives us only half the picture.

Using marginalised groups for medical research

Progress in medicine has too often historically been built on the pain and suffering of an unwilling person. James Marion Sims, credited as the father of gynaecology, developed techniques to address complications in childbirth, by experimenting on black enslaved women and girls. The experiments were performed without anaesthetics so they could be ‘perfected’ before being performed on white patients. The exploitation of societies marginalised bodies for the benefit of others has been a feature in medicine across history. Most grossly manifesting in the ‘experiments’ inflicted upon victims in Nazi concentration camps.

It is important to bear this historical context in mind before examining the values the Artificially Intelligent healthcare is built on.

Health must be quantified.

AI in healthcare is a product of data. I have discussed in previous articles the ‘Garbage In, Garbage Out’ principle that if you don’t put quality and varied data into the algorithms you will get garbage analysis out of them. The key advantage of AI in healthcare is accessing and analysing data faster. For this to be a valuable exercise we must collect the right data.

This rests on the inbuilt value that health can be quantified. That ‘healthy’ can be defined in a series of numbers. Numbers become a proxy for good or bad. Health becomes defined through numbers such as BMI, blood pressure, heart rate. What is measured is managed. But not all aspects of health can be measured, the body is not a machine. We have an ever-increasing amount of information about our bodies, but data does not automatically lead to knowledge and knowledge does not automatically lead to wisdom. The numbers can only tell us so much. It is a philosophical debate if health, like other concepts such as joy, pain or productivity can ever truly be measured or quantified.

Privacy must be subjugated.

So where is all this data coming from? In the past studies and research were done on a select group, who were ‘representative’ to a greater or lesser extent, of the population. This method does not generate enough data to feed the AI algorithms. Data is now being collected on mass by governments, health care systems and private companies. Sometimes with your consent, sometimes without it.

In England all patient GP records are now shared centrally for the purpose of research with the NHS. It is possible to opt out but that relies on a certain level of awareness and concern before action. The NHS reassuringly confirms that data will not be used for “solely commercial purposes”, implying it can be used for partial or mostly commercial ones.

Many health insurers or life insurers offer ‘free’ wearable tech such as Apple watches. As the saying goes, if the tech is free, you are the product. The data from these wearables is used to perfect and adjust insurance premiums. Even if you feel comfortable sharing your health data now, that could change. You could become sick in a way which could put your job at risk. Or the laws could change. The use of period trackers in the US has recently become controversial after the overturning of Roe Vs Wade, as they would be subject to subpoenas and their data potentially used as evidence to convict women who are seeking an abortion.

You may not even be supplying medical data. AI has been applied to social media posts to diagnosis mental health conditions and neurological diversity. The data from your phone was used during the covid-19 pandemic to monitor compliance with various lock downs.

There is a point where we are comfortable with a small infringement of our personal privacy towards a greater good. I can get onboard with providing some of my data if it will help cure cancer. But –

What about the government having full access to all my health records?

What if it was leaked or hacked?

How do I feel about my social media posts and phone movement data being used being scanned and scoured by private companies to extract health insights?

What if the findings of that data led to my rights being infringed?

We need to ask ourselves as a society where we draw the line between personal privacy and collective health, and how much that line will need to move now that healthcare is so reliant on huge volumes of data.

The Hippocratic Oath must change.

Hippocrates referred to as the ‘Father of Medicine’ separated medicine from religion and pushed it into the realm of men, something humans can understand and influence. Does AI push it out into the realm of machines?

The Hippocratic oath is a statement of ethical intent by physicians which requires confidentiality and non-maleficence. As we have seen above the value of medical confidentiality is already breaking. Non-maleficence, or the “first do no harm” principle seems obvious in the context of healthcare, but society has many examples where healthcare adjacent organisations have intentionally allowed harm. The opioid crisis in the US is the direct result of the nefarious practises of the Sackler family, who promoted Oxytocin, delivering them over $13 billion of profit and causing untold pain and suffering.

Data and algorithms will work alongside or potentially replace physicians in providing your healthcare. An algorithm cannot take an oath to do no harm. It can only do what it is instructed to do. So, should the programmers take an oath to do no harm? What about the companies providing the AI healthcare service?

While physicians do break the Hippocratic oath, most recently and horrifically in the news the case of a midwife harming new-borns. They are ultimately limited in the scale of damage they can cause. Dozens or perhaps hundreds of people can be hurt, but not millions. The risk with AI is the speed and the scale of impact. I trust the doctors who care for me have my best interests at heart. But AI can be a black box. You must trust the person who programmed it. If the AI code is the company’s intellectual property and a secret, would regulators still be able to review it? Some AI is so opaque that not even those who built it understand how it identifies patterns or predicts outcomes. How can you then be sure that your best interests are in the code?

So, is AI healthcare Artificial?

Sort of. It requires human data and human trainers to extract meaning from that data. It needs humans to tell it what to value. However, the speed and scale at which it can operate is truly artificial. Not only that but it is able to identify patterns that would not have been picked up by a person.

Is AI healthcare Intelligent?

It can certainly spot patterns and make predications, both at scale and at speed. But it lacks the emotional intelligence of human carers, and empathy is critical to the healing process. It also lacks its own will and intent. It cannot decide whether to heal you, it can only do what it is programmed to do.

Is AI healthcare ethical?

It could save millions of lives and keep us all healthier for longer. But we have to manage the trade offs:

The necessary reduction in privacy needs to be tightly regulated with extensive checks and balances.

The aim should be health rather than profit, so any health service which uses AI should have democratic oversight and public funding.

We should consider an AI Hippocratic Oath or require the programmers to follow one.

But yes, it could be ethical, and that is very exciting.

If you enjoyed this article, please consider reading others in the AI ethics series.

1. AI knowledge: Is chatGPT smarter than you?

2. AI drivers: Is Tesla the going anywhere?

3. AI can see you: Facial Recognition is watching.

4. Dr. AI: The machine will heal you.

5. The bank of AI? 18/3/23

6. Algorithmic decisions – Bureaucracy of AI? 25/3/23

7. Chatbots – AI friends? 1/4/23

8. Deepfakes – AI faces? 8/4/23

9. Targeted marketing – The AI nudge? 15/4/23

10. Generative AI – The AI artist? 22/4/23

Great post yet again! Recently at a conference on The Future of Privacy there was a medical student who asked about potential collection of newborn babies genetic data to irradicate certain genetic diseases (I can't remember the details off the top of my head) and one of the speakers, a legal expert, pointed to the ethical implications of using the data of someone who cannot consent (babies in this case) and what that might mean for their futures as adults. What was most interesting to me was that the medical student spoke of this data collection as revolutionary and failed to see the possible ethical implications, whilst the speaker was immediately alarmed. I think this speaks to your point about whether programmers need to take a Hippocratic Oath and the need to make transparent what happens to the data when it is collected, what will it be used for in future etc. I think these questions need to be addressed now, particularly for future generations whose information is digitised at a young age and therefore are more at risk.